Editor’s note: Tiare Silvasy is a master’s student in Tropical Plant and Soil Sciences at the University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa who participated in a Trellis Fund project led by the Center for Agricultural Research and Development (CARD-Nepal). She recently returned from a trip to Nepal to work on this project, which focused on soil testing and nutrient management for smallholder farmers — many of whom had never had a soil test before. Here’s a Q&A with highlights from her trip.

Question: How does your work on this Trellis Fund project fit into your studies and career?

Tiare Silvasy: In Hawaii, my thesis is on nutrient management and I’m looking at local organic fertilizers, specifically at meat and bone meal, produced locally here from the islands’ fish and meat wastes. We’re looking at using those local materials on our farmer’s fields, instead of importing fertilizer products. Meat and bone meal contain a relatively high amount of nitrogen for an organic fertilizer.

Tell us about the main work you did on this Trellis Fund project during this trip.

The farmers we met with in Nepal had never had a soil test done and didn’t really know what their soil’s baseline nutrients were. A lot of them are using farmyard manure produced from dung from their animals, and putting it on their fields.

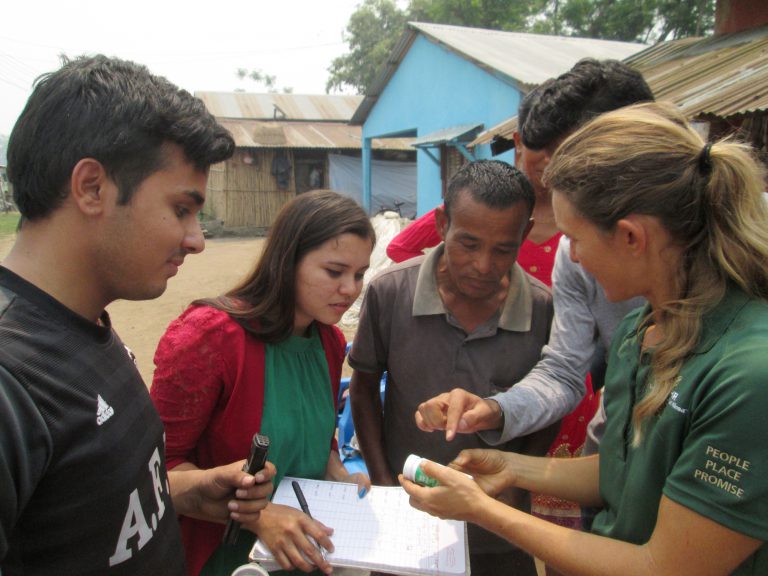

The day after we arrived, we started with the field work. For two groups of farmers, we repeated this routine: one day soil testing and another day farmer training.

Our training was PowerPoint presentations and hands-on demonstrations. The team from CARD-Nepal had presentations in Nepali; Rajendra Regmi presented on pest control and Sameer Magar presented on nutrient management. My presentation was about using crop rotation to improve pest and nutrient management in English, and they translated for me.

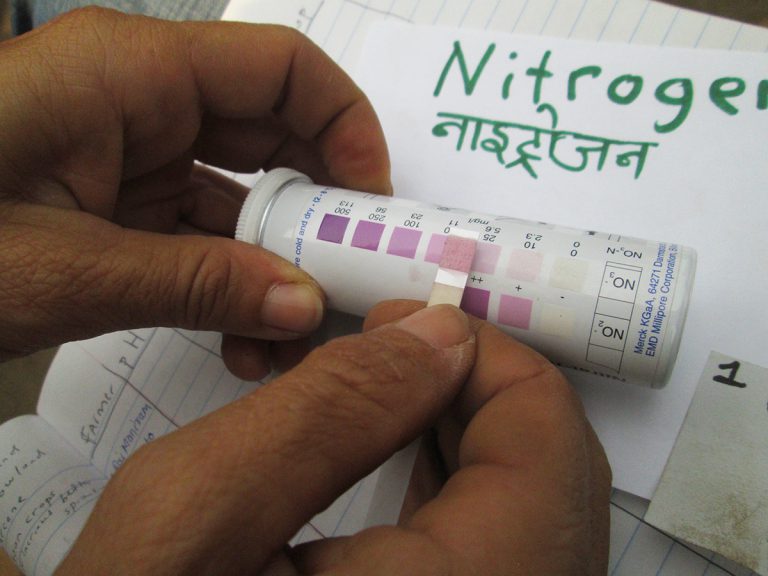

Some farmers brought a soil sample to us, or we would visit their farm and do a soil sampling demonstration to show them how to do it. All of the farmers in these villages were within walking distance. There were at least 20 farmers in each group. Between the two groups, we did 46 soil samples total. We had a pH meter and color test strips for nitrogen, phosphorus and potassium. Most of their soil was sandy texture, maybe of the Inceptisols order in soil taxonomy.

We broke our soil test results into three broad categories and recommendations. Either:

- your soil is a little deficient and you should add nutrients

- your soil is in a good range

- your soil results were high, don’t add fertilizer

The farmers were really interested to see the results and understand the interpretation. A lot of them used farmyard manure as their only input.

We also sat down with the farmers and did surveys, which I developed before I went to Nepal along with Rajan Ghimire (of CARD-Nepal). That’s how we found out most of the farmers had never done soil testing before, so it’s good to have that documented. There was only one farmer we found through the survey was using sesbania as a green manure; we use a lot of green manures here in America, and that could cut the farmer’s fertilizer needs significantly.

Going forward, we’re going to develop a poster and a manual, for soil testing and understanding the results. And I’m planning to present a scientific poster on this project at the American Society for Horticultural Science conference this summer.

Were there any surprises in your work?

One big surprise to me was when I visited the soil science lab at the Agriculture and Forestry University (AFU) in Rampur where the students I was working with study, they had a few machines but really had little to no equipment, so the stuff that I brought with me was a really big help and we were able to purchase additional supplies at a local farm distributor shop. I was kind of surprised at their lack of access to technology. Earlier in the project, I was looking at the list of people I would be working with — many are soil scientists with Ph.D.s — and I was wondering, what am I going to bring to the project? So I was glad to see the equipment [purchased with a Trellis Fund supplemental student fellowship] was especially useful.

Does this experience change what you think about working internationally?

I’ve done a couple of projects internationally, always integrating farming projects with my own travel. I started WWOOFing in Costa Rica, and then also worked in permaculture in Australia, and did some projects in Panama and Colombia.

I would like to do more work like this in the future. When I graduate I want to work in teaching, research and extension. I had a good experience on this project, and it just makes me want to do more of this kind of work.

What would you say to other students who might be considering participating in a Trellis project, in the future? Any advice?

I would say it’s a really great opportunity for students who have a service-oriented mind and want to travel and engage in projects internationally. I was excited to learn about this opportunity because as a student you can’t take a lot of time off. But to go for just 2 weeks and have a meaningful protect to work on and your plane ticket taken care of — that’s big.

The Trellis Fund is managed by the Horticulture Innovation Lab at UC Davis, in partnership NC State, UH Mānoa and UF. The Horticulture Innovation Lab is funded by the U.S. Agency for International Development, as part of Feed the Future, the U.S. government’s global hunger and food security initiative.

Video above: Tiare Silvasy made a short video about her experiences doing soil testing for farmers in Nepal with the Eco-Minions student club and the Center for Agriculture and Research Development (CARD-Nepal), as part of a Trellis Fund project.

More information:

- Trellis Fund webpage

- 2016-2017 Students: Students selected for projects in Ghana, Uganda, Kenya, Nepal, Cambodia

- 2016-2017 Projects selected: Nine new Trellis Fund projects awarded

- Fact sheet: 2016-2017 Trellis Fund fact sheet (PDF)

- Recent blog posts about the Trellis Fund