Editor's note: This blog post by Kate Scow is based on a presentation she gave at the International Research Conference held at UC Davis on Sept. 17-18, 2018. Co-authors of the presentation include Abe Salomon, Betty Ikalany, Helen Acuku, Mariah Coley and Julia Jordan.

The presentation includes insights from the Horticulture Innovation Lab project led by Scow, which focuses on developing farmer-led irrigation solutions in Uganda. In addition to discussing participatory research, this presentation also includes lessons learned related to irrigation and women farmers in Uganda.

Participatory research to address sustainable development challenges

Meet Teddy, a woman farmer in Uganda interested in irrigation

Teddy Atiang is a farmer in eastern Uganda. She farms crops on her husband’s land, but would like to lease her own plot to grow more food and make income for school fees. She knows growing rainfed vegetables is hard, as weather is changing and rainfall unpredictable. Irrigation could help a lot. But adopting irrigation has challenges especially for women farmers like Teddy.

One challenge is having enough time. Teddy’s family responsibilities mean she has a lot of work in the household before she can head to the field — cooking, childcare, getting water. The window of time she has to irrigate is narrow. It is also hard for her to access good land. Women may need flexibility in leasing — renting small parcels, paying in installments, and negotiating a favorable price. Landlords are not always willing to accommodate these needs. Compared to women, men in general have more freedom in use of their time and certainly greater access to land.

Sharing water is a major challenge; irrigation is not just about technology. Without simultaneously creating local governance organizations, it can mean that some farmers, especially women, may not get access to water and technologies.

Our project was funded by the Horticulture Innovation Lab to work in eastern Uganda on innovation and implementation of small-scale irrigation technologies and social institutions with smallholder farmers engaged in horticulture. We use a participatory research approach.

What is participatory research?

First, what is NOT participatory research: Bringing in a pre-existing technology, training farmers to use it and then measuring how effective it is and perhaps comparing different variations. You can count all the people in the trainings, but there is no guarantee it is of interest or adopted.

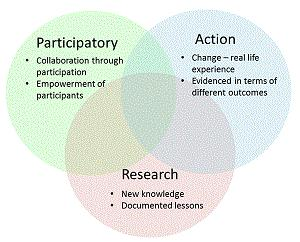

The general principles of participatory research combine:

- Research — generating knowledge

- Participation — collaboration and empowerment

- Action — social change through the process

Farmers are members of the research endeavor, as opposed to their serving only as sources of data. Investigators are also participants, along with other stakeholders

The concept of “learning by doing” is crucial and recognizes that everyone learns and changes through active adaptation of their existing knowledge with influx of new information.

In its purest form, all participants are involved throughout the entire research process: from design to analysis and evaluation. This is hard. What often happens is different degrees of involvement of different participants at different points, while preserving the principles of participatory research.

How did we implement participatory research in our project?

We work with six large farmer groups in eastern Uganda, along with a local non-governmental organization that works with women in rural communities, an irrigation NGO, governmental research and extension organizations, and a local university with a program in irrigation engineering. (See list of project partners.)

We engage with farmers to develop and test irrigation innovations appropriate for their particular environmental and social conditions.

Each group followed the same general process but in different ways with different outcomes: Farmers and partners shared current knowledge and irrigation practices, then identified technologies of interest. With input from technical experts, they designed systems, chose technologies and organized social structures to employ the new irrigation practices. Then the farmers and partners went through the process of implementation, reflection, redesign, and if necessary repeating this iterative process.

What we have learned about irrigation technologies

- Having a local university involved (in this case Busitema University) is a win-win for engineering students collaborating with farmers to solve problems in the field.

- Having a trial and error process rather than “design and train” was needed in almost every case, as all technologies needed iterations, sometimes going as far as needing to tear out and replace an original design

- Combinations of existing technologies, rather than entirely new ones, was sometimes the innovation. One example was use of micro-basins, a traditional irrigation technology, at one site where farmers decided to combine micro-basins with a sprinkler system. More water infiltrated into the soil rather than ran off, so much less water was needed — along with less fuel and time to pump water. Farmers saw immediate benefit and expanded this technology combination across their fields. The participatory research process made this possible.

What we have learned about women’s challenges

Women represented at least 50 percent of the engaged farmers and played major roles in all aspects of project, including in leadership positions and on all governance committees. Partners with the Teso Women Development Initiatives ensured women’s voices were heard.

- Women's time and scheduling: The participatory process ensured that important decisions were made, when women could attend the meetings and ensure planning considered women’s schedules. One group having trouble scheduling and getting access to shared irrigation equipment used resources from their savings group to buy a pump dedicated for women’s use and run by a woman operator.

- Land access for women: At a site near Jinja where women had trouble getting land, they created a collective to lease a larger parcel of land that they divided among themselves, and created a dedicated savings group to regulate the funds. This tripled the number of women farming on their own plots.

Challenges of participatory research

Tensions between original research plans and desires of increasingly engaged and empowered farmers over time are common.

The process of trial and error, though effective at finding solutions, is not easily accommodated by traditional research methods. Innovations often build on each other at the level of a site and are hard to evaluate as independent interventions. This may require changing the focus of research to be more centered on the process.

Social challenges and complexity not visible in more traditional research project may emerge in participatory research, e.g., someone trying to take advantage of the system. These complexities usually become more visible, and with governance systems the group can call it out and address before it is too late.

What about scaling?

Nothing is more convincing to farmers than other farmers with tangible successes. A participatory process grows farmers who are experts and leaders. Having different locations comparing different approaches creates a powerful network of demonstration sites.

Our project team is documenting findings in technology briefs, blogs, a new website, and an irrigation app to guide decision making. We don’t want to gloss over the variations in social, economic and ecological contexts and the need for local adaptation. We think silver bullets are rare. So part of what we communicate is the participatory process to discover irrigation solutions.

Having local government, research organizations and NGOs as participants from the start make them advocates and liaisons to get the word out about irrigation solutions. They own it too. They bring groups to meet the farmers involved in the project and see their sites. At two project sites, local government leaders want to ride on the success and are now helping fund farmers to extend the irrigation infrastructure and increase capacity at the sites.

What’s next for participatory research – and Teddy, the Ugandan farmer

There is growing support for participatory approaches. Research conducted by several development agencies (including the World Bank and USAID) suggests many benefits are gained through the use of participatory approaches. While participatory projects may have higher start-up costs, they will be less expensive and more sustainable in the long run.

Teddy has grown as a leader through our participatory process and was recently re-elected chairperson of her farmer group. She is a charismatic and convincing spokesperson for the innovations coming from her community, which now provides a foundation that local government and NGOs can build on.